Physiker enthüllen das Geheimnis gefangener Wellen

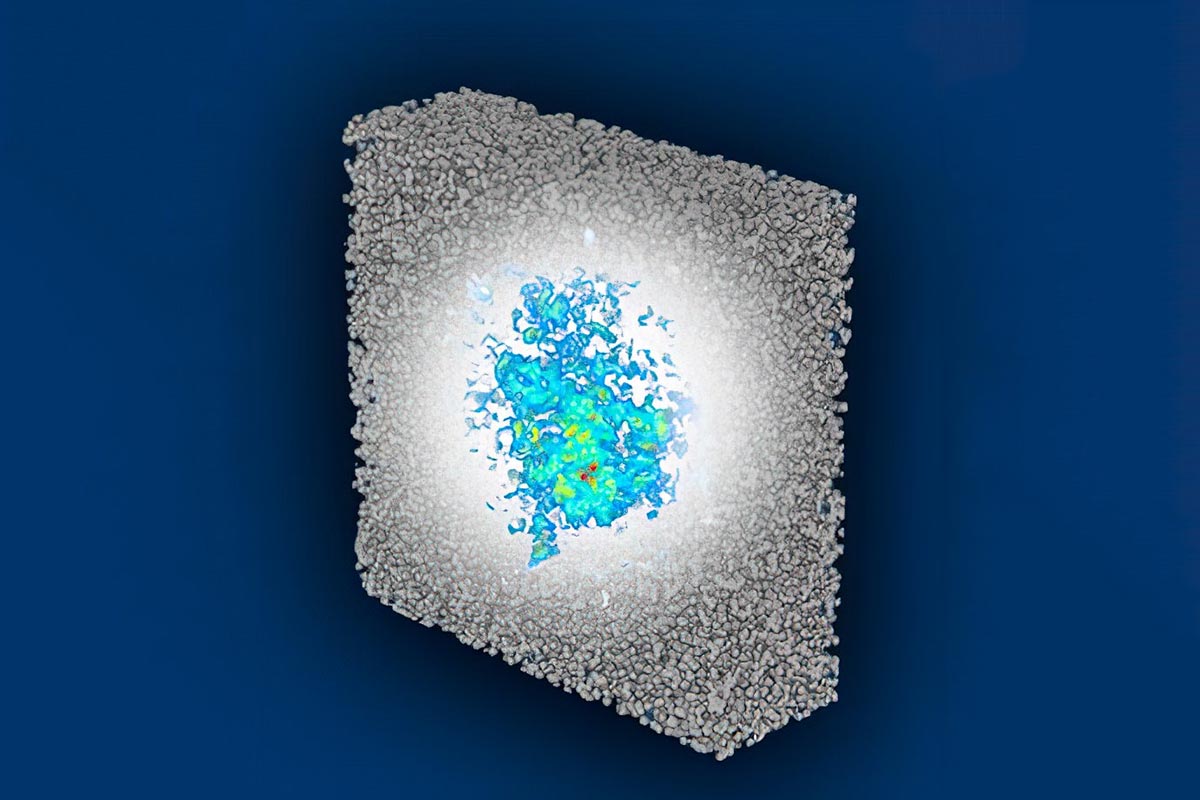

Fortschrittliches Rechnen hat Forschern dabei geholfen, ein jahrzehntealtes Rätsel über die Lokalisierung von Licht in 3D-Strukturen zu lösen. Die Studie ergab, dass Licht in zufälligen Packungen metallischer Kugeln eingefangen oder „lokalisiert“ werden kann, was den Weg für mögliche Entwicklungen bei Lasern und Photokatalysatoren ebnet. Bildnachweis: Yale University

Ein Forscherteam hat eine bemerkenswerte Steigerung der Rechenleistung genutzt, um ein jahrzehntealtes Rätsel zu lösen, das die Möglichkeit betrifft, Lichtwellen in dreidimensionalen Strukturen zufällig gepackter Mikro- oder Nanopartikel einzufangen. Diese bahnbrechende Entdeckung könnte unter anderem zu Entwicklungen bei Lasern und Photokatalysatoren führen.

Die Elektronen im Material können sich entweder frei bewegen, um Strom zu leiten, oder sie können eingefangen werden und als Isolatoren wirken. Dies hängt von der Menge der im Material vorhandenen zufällig verteilten Fehler ab. Als dieses als Anderson-Lokalisierung bekannte Konzept 1958 von Philip W. Anderson vorgeschlagen wurde, erwies es sich als bahnbrechend für die zeitgenössische kondensierte Physik. Die Theorie umfasste sowohl den Quantenbereich als auch den klassischen Bereich, einschließlich Elektronen, Schallwellen, Wasser und Schwerkraft.

Allerdings ist trotz 40 Jahren intensiver Studien nicht genau geklärt, wie dieses Prinzip beim Einfangen oder Lokalisieren elektromagnetischer Wellen in drei Dimensionen zum Tragen kommt. Unter der Leitung von Professor Hui Cao liefern Forscher endlich eine endgültige Antwort darauf, ob Licht in drei Dimensionen lokalisiert werden kann. Es handelt sich um eine Entdeckung, die mithilfe der lokalen 3D-Beleuchtung vielfältige Möglichkeiten sowohl für die Grundlagenforschung als auch für praktische Anwendungen eröffnen könnte. Die Ergebnisse wurden am 15. Juni veröffentlicht The quest for 3D Anderson localization of the electromagnetic waves has spanned several decades with numerous attempts and failures. There were multiple experimental reports of 3D light localization, but they were all questioned due to experimental artifacts, or the observed phenomena were attributed to physical effects other than localization. These failures led to an intense debate on whether Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves even exists in 3D random systems. Since it is extremely difficult to eliminate all experimental artifacts to get conclusive results, Cao and her coworkers resorted to the “indignity of numerical simulation,” as Philip W. Anderson put it in his 1977 Nobel Prize lecture. However, running computer simulations of Anderson localization in three-dimensions has long proved challenging.

“We could not simulate large, three-dimensional systems because we don’t have enough computing power and memory,” said Cao, the John C. Malone Professor of Applied Physics and Professor of Electrical Engineering and of Physics. “And people have been trying various numerical methods. But it was not possible to simulate such a large system to really show whether there is localization or not.”

But then Cao’s team recently teamed up with Flexcompute, a company that had a recent breakthrough in accelerating numerical solutions by orders of magnitude with their FDTD Software Tidy3D.

“It’s amazing how fast the Flexcompute numerical solver runs,” she said. “Some simulations that we expect would take days to do, it can do in just 30 minutes. This allows us to simulate many different random configurations, different system sizes, and different structural parameters to see whether we can get three-dimensional localization of light.”

Cao assembled an international team that included her longtime collaborator Prof. Alexey Yamilov at Missouri University of Science and Technology and Dr. Sergey Skipetrov from University of Grenoble Alpes in France. They worked closely with Prof. Zongfu Yu at University of Wisconsin, Dr. Tyler Hughes, and Dr. Momchil Minkov at Flexcompute.

Free of all artifacts that have previously marred experimental data, their study closes the long debate about the possibility of light localization in three dimensions with accurate numerical results. First, they showed that it is impossible to localize light in three-dimensional random aggregates of particles made of dielectric materials such as glass or silicon, which explained the failures of the intense experimental efforts in the past several decades. Secondly, they presented the unambiguous evidence of Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves in random packings of metallic spheres.

“When we saw Anderson localization in the numerical simulation, we were thrilled,” Cao said. “It was incredible, considering that there has been such a long pursuit by the scientific community.”

Metallic systems have long been ignored due to their absorption of light. But even considering the loss of common metals such as aluminum, silver and copper, Anderson localization persists.

“Surprisingly, even though the loss was not small, we can still see the evidence of Anderson localization. That means this is a very robust and strong effect.”

Besides resolving some long-standing questions, the research opens new possibilities for lasers and photocatalysts.

“Three-dimensional confinement of light in porous metals can enhance optical nonlinearities, light-matter interactions, and control random lasing as well as targeted energy deposition.” Cao said. “So we expect there could be a lot of applications.”

Reference: “Anderson localization of electromagnetic waves in three dimensions” by Alexey Yamilov, Sergey E. Skipetrov, Tyler W. Hughes, Momchil Minkov, Zongfu Yu and Hui Cao, 15 June 2023, Nature Physics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-023-02091-7

„Böser Kaffee-Nerd. Analyst. Unheilbarer Speckpraktiker. Totaler Twitter-Fan. Typischer Essensliebhaber.“